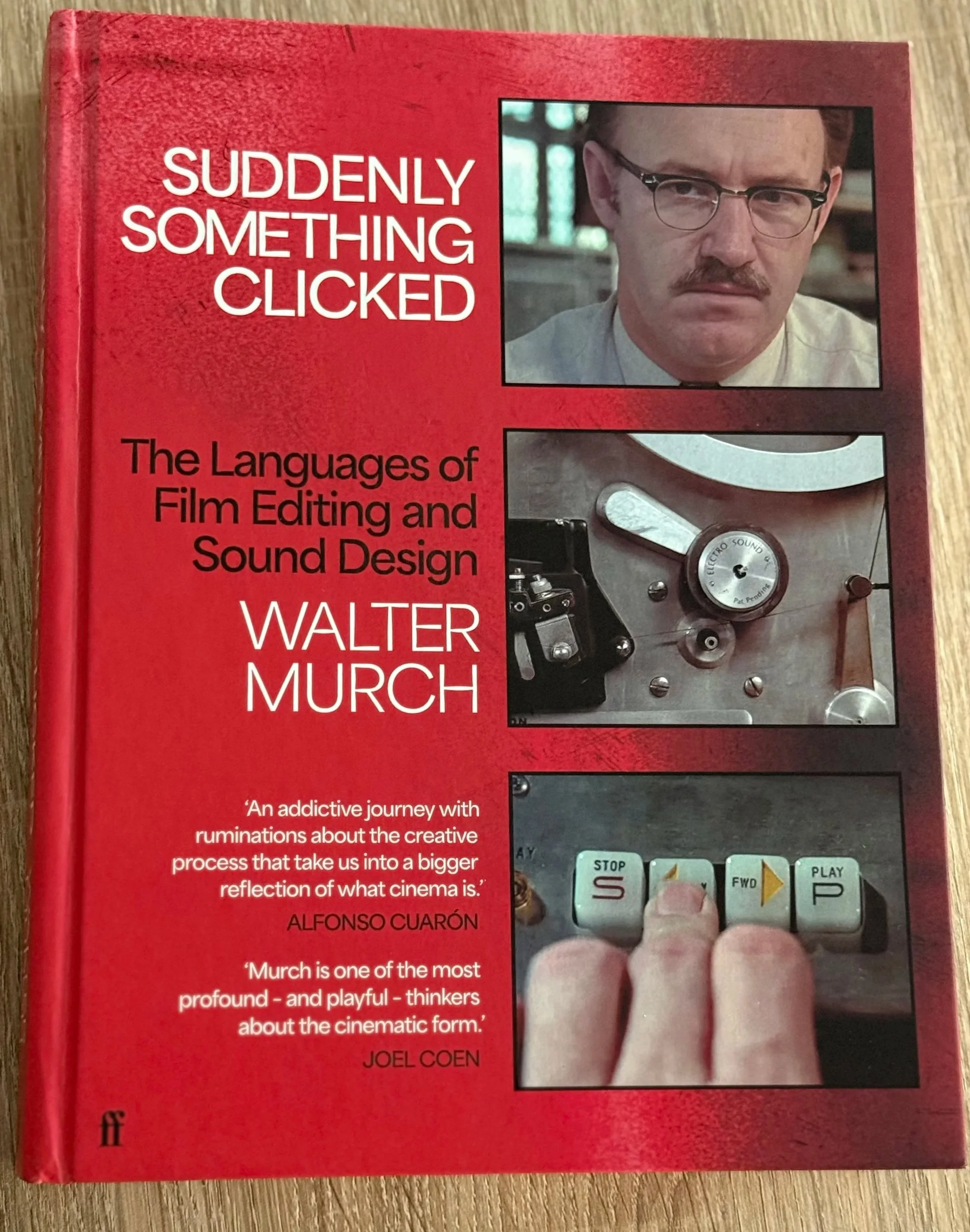

For those of us who work in post-production (particularly as editors or sound designers), the name Walter Murch may be a familiar one. With a career spanning over 60 years editing and sound mixing films such as American Graffiti, The Godfather films, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now, to name a few, Murch has amassed a lifetime’s worth of knowledge and theory, which he so willingly chooses to share with others. And for film editing nerds who enjoyed his first book, In the Blink of an Eye, you’ll be pleased to learn that Murch has just released his latest work: Suddenly Something Clicked — The Languages of Film Editing and Sound Design.

Suddenly Something Clicked - by Walter Murch

Published earlier this summer, Suddenly Something Clicked is actually just part one of a trilogy he has recently written, with the next volumes to be released at a later date. These upcoming books will cover other topics related to film production, other than just editing and sound design.

If you are looking for a detailed, technical manual on techniques or software, Suddenly Something Clicked isn’t that book. Instead, Murch expertly blends theory, philosophy, and personal anecdotes to illustrate his process for approaching a film’s edit, while also sharing some pitfalls he has encountered during his long career. He is equal parts philosophical and intellectual when it comes to the subject of film, even devoting an entire chapter to comparing the process of editing to the way DNA, RNA, and ribosomes interact in our cells. And yet, the book reads as easily as a light novel for any movie history aficionado — particularly if you are at least somewhat familiar with the process of editing and mixing films.

And for those who do consider themselves movie history buffs, you’ll immediately recognize that Walter Murch started his career working with directors like Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas during their American Zoetrope years in the early 1970s. It was during this period when the landscape of film and filmmaking was beginning to change, as the old Hollywood studio system began to give way to more independent artistic voices, ushering in an era that revolutionized both how films were made and how audiences experienced them.

The book gave me a new appreciation for what Coppola, Lucas, Murch, and their peers at American Zoetrope were doing when they decided to leave Hollywood behind for the cool climate of San Francisco to start an independent film company — a kind of punk-rock move in an era before punk-rock. The result? Some of the most groundbreaking films ever put on screen, created while bravely diving into new techniques that drove the medium forward. Murch recalls pushing the limits of the dynamic range of optical film soundtracks at the time, as well as helping to develop a six-channel mix for Apocalypse Now, which would become the precursor to modern 5.1 surround formats. He is even credited with coining the term “sound designer,” becoming the first person ever to receive that credit.

Although Murch notes that this type of innovation didn’t come without a certain amount of trepidation: “I was overwhelmed by all the ideas…But I had also learned by now that when life proposes to push you out of your comfort zone, it is usually a good idea to take up the offer.”

The book is also peppered with quotes from various sources at the bottom of every page. This one is credited to Pablo Picasso

My biggest takeaway from reading about Murch’s experience in those days was the freedom a director like Francis Coppola gave him to experiment — trying version after version, edit after edit, until things felt right. If there is a common thread to Walter Murch’s work in the 70s, it’s how much he experimented in the edit room, constantly learning and trying out new technology. He and his colleagues even built a mixing room from scratch for Apocalypse Now to accommodate the film’s innovative six-channel soundtrack, then tested mixes in a local theater, unsure whether everything would work.

Nowadays, specialists in post-production (whether editors, sound mixers, or others) are almost expected to function like a machine. A client wants X-result? Just punch in A, B, C and out comes X. And yes, part of the job is knowing exactly how to deliver that result, especially in advertising and marketing, where the end goal may simply be to make a product — or “content.” But when every project is approached this way, it leaves little room for experimentation or discovery.

Art doesn’t work that way. Suddenly Something Clicked reminds us that limits themselves aren’t the enemy — in fact, creativity is often born from them. The key difference is whether those limits give you space to explore or box you in. Murch thrived because directors like Coppola gave him both the framework of a project, and the trust to experiment and discover within those boundaries. And it is within that balance that artists thrive.

Walter Murch - experimenting…